Burn the boats

Action defines organizations

Larger companies often become known for what they will not do. Smaller firms are defined by what they will do. The comparisons are widely know, but are worthy of a reminder:

Blockbuster + Netflix. Nokia + Apple. Cabs + Uber.

The asymmetrical themes are generally uniform: One brand is known for hubris, privilege, hierarchy, and entrenchment, while the other is associated with curiosity, eagerness, empowerment and sparing no effort. Said another way: larger organizations make decisions based on what they are not willing to lose, and upstarts are wholly focused on what is to be created. Boeing is now synonymous with inaction. SpaceX is renowned for innovation.

While the historical context surrounding the phrase “Burn The Boats” is a bit loose, the imagery and meaning is clear: commitment to a strategy is not an act of moderation. This is why hedge fund activity deserves attention: it represents extensive dedication with true skin in the game. The challenge is that by the time an activist makes an investment, they have already won. Typically a beleaguered railroad stock will receive a bump of 10% to 40% following an investor initiating a public position. Thus, if the investors have already gained upside, the question for the targeted railroad (and, to some extent, the industry at large) seems to become: how to avoid losing altogether?

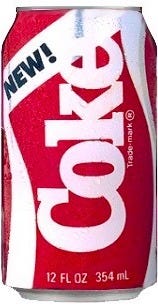

There is an argument to be made for playing the game of hedge fund chess. Board expansions, cost reductions, shuffling of leaders, and sourcing public and regulatory support are all methods out of the traditional playbook. However, as many question the true efficacy of corporate activism, it is also fair to question the effectiveness of executing the same decisions internally under the guise of strategy. Sure, New Coke or “Coke II” carried new branding and a purportedly reformulated recipe. The negative health effects were nonetheless the same.

The ironic aspect of proxy battles lies within agency + influence. One side actually controls results based on leadership and performance. The other is relegated to yelling from the sidelines. Thus, what is the antidote when every prescription tastes like poison? Burn the boats. Play a different game altogether.

Sell the jets

The first move of seemingly every activist v. corporation playbook is bottom line reduction. Quantitatively, this makes sense: revenue expansion often takes time whereas cost controls are immediate. Layoffs, expenditure controls, and travel restrictions are all well-applied levers. However, this does raise the question about proximity to customers and plans for true, long-term growth resulting from those partnerships. If large companies are traditionally defined by what they will not do, then what are the lingering line-items often left untouched? Private jets.

After United Airlines CEO Scott Kirby gained notoriety for taking a private plane during a service meltdown where passengers and employees were stranded for days, it raised an interesting question: why not use the opportunity to get closer to the operation? For railroads, this is a particularly useful question, as most continue to own and maintain fleets of equipment designed to house and feed employees and dignitaries anywhere there are two rails separated by a standard gauge. If there is capacity in the network for more volume, then there is likely space on the calendar to see the operations personally. The opportunity to understand the needs of the shipping community from a grain loop in the Dakotas or a siding in Dearborn, Michigan is unrivaled.

Go to your users

One unique concept of selling transportation as a service product is that both your team members and your customers often overlap in the physical world. Co-location is a natural byproduct. Thus, arguably the best place for leaders to understand the disconnect between markets, customers, team members and results is out in the field.

A prime illustration of simply going to your users is highlighted in Reid Hoffman’s interview with Airbnb’s Brian Chesky: Do things that don’t scale. In the discussion, Brian references a particularly illuminating conversation with Y Combinator co-founder, Paul Graham.

And he said something I’ll never forget. He said, “So your users are in New York and you’re still in Mountain View.”

I said, “Yeah.” And he said, “What are you still doing here?”

And I go, “What do you mean?”

He said, “Go to your users. Get to know them. Get your customers one by one.”

And I said, “But that won’t scale. If we’re huge and we have millions of customers we can’t meet every customer.”

And he said, “That’s exactly why you should do it now, because this is the only time you’ll ever be small enough that you can meet all your customers, get to know them, and make something directly for them.”

The market, by and large, is asking for something different from railroads: higher financial return, improved service performance, greater ease of use. Disregard, for a moment, that these notions may be highly interdependent. What better place to seek and encourage growth in these areas than in the exact places where the relationships are being tested and the work is being completed? If you work at a railroad, go see your customers. If you are fortunate to lead at a railroad, double-down and go see both your team and your customers. Third shift at Enola or North Platte or Valdosta or Argentine offers a particularly educational experience. Go find out for yourself and repeat until the quarterly results match your targets.

That’s the challenge with burning the boats, though. Undertaking actions that others, such as money managers boasting of operational expertise, find too challenging, or are reluctant to perform can be immensely rewarding. Trips to the field or visits to customers in distant locations require tradeoffs in the overscheduled rhythm and relative comfort of corporate railroading. Trading the jets for the company train serves as a powerful equalizer by deeply engaging every team member in the true task at hand: growing and improving the railroad. It leaves little room for doubt in the mission and even less for entitlements. Privilege becomes a cultural disease. Which is exactly what happened to Boeing. An organization becomes what it tolerates.