Game-changing: College Football's Lesson in Beating Organizational Inertia

College football has finally returned. With it, the majority of the NCAA’s $20B earnings is on a trajectory to hit new records. Yet, less than a year ago, critiques and commonly held beliefs would have led even the most casual observer to believe that collegiate football was on a downhill run. This theme is not too dissimilar from when Nebraska and Texas A&M broke for new conferences over a decade ago. Fans lamented changes then, as they do now.

This year, though, adjustments in rules and regulations - which allow players to receive more value for the upside created for their institutions, and face fewer restrictions and limitations for transferring - frustrated many. Some, however, claimed that the transfer portal was ruining college football and the addition of name, image, and likeness would lead to a collegiate implosion.. Jeff Caliva, LSU superfan, summarized the behavior adequately for the Wall Street Journal:

On Sunday through Friday, I complain, and I don’t love the changes to college football. But on Saturday, it doesn’t matter. I don’t care about NIL when the games turn on. All that stuff goes away and it’s just college football.

Yet, the lingering concern has always been: What is the real issue with change? Fundamentally, the concept of the game on the field is relatively unaltered, but the end product for the fan is much improved. The truth is that humans struggle with change, and, as the proverb goes, old habits die hard. This has never been more true than in some of the most prominent organizations in the world. Groups with proud legacies are often the most resistant to change.

As a part of the corporate lifecycle, organizations typically expand as they become more successful. As people become more numerous, processes are usually added for the sake of efficiency, repeatability, and safety. Why fix the machine if it is not broken? is a phrase uttered by many simply because there are two well-incentivized cognitive functions at play: recency bias and loss aversion.

Often, this encourages executive teams to strongly pursue tried and true, core levers:

Revenue generation; often in the form of broad price increases (for existing or new-but-similar services)

Expense reduction, through workforce reductions, equipment rationalization

Innovation deferment, by pivoting from highly probable improvements to precise actions from the past

Without a doubt, the pursuit of profitability is a winning strategy. And in a world where most are judged by their most recent record, there is a strong inclination to simply run the same successful playbook from prior quarters. This narrative tends to reinforce what most tenured employees in large organizations know but never say: just do enough to score a few points, but never take a risk. The incentives at most organizations trend against risk taking because the incentives are always in favor of being right versus getting it right. Moving the chains via an inside zone is often looked upon more favorably out of a desire for the illusion of progress instead of a post route, which is a much more efficient, but riskier, path to points.

In a world overrun with opinions and quarterly analyses on corporate performance, it is hard to imagine how any leadership team manages to shrug off the fickle crowds of spreadsheet jockeys jeering from the sidelines and courageously commit to a long-term strategy. Everyone wants to win now, but they are typically unwilling to commit to the multi-year actions that truly compel an organization to perennial success. Paraphrasing, but as Nick Saban once remarked, everyone wants to be the beast until it comes time to do what beasts do.

One of the reasons we enjoy box scores and corporate earnings statements is cognitive ease. It offers humans the ability to forget about the minutes, days, and weeks of practice or process, which tend to yield a specific result: preparedness. By nature, we prefer the certainty of a discrete number or explicit pass / fail versus the multi-step process of experimentation or evolution. This is why organizations that incentivize progress towards perfection can outperform those who focus solely on perfection. Being right instead of working to get it right. By default, the easiest way to ensure a higher probability of being right is to ensure you are never wrong. When the desire to not lose is stronger than the will to win, that’s inertia.

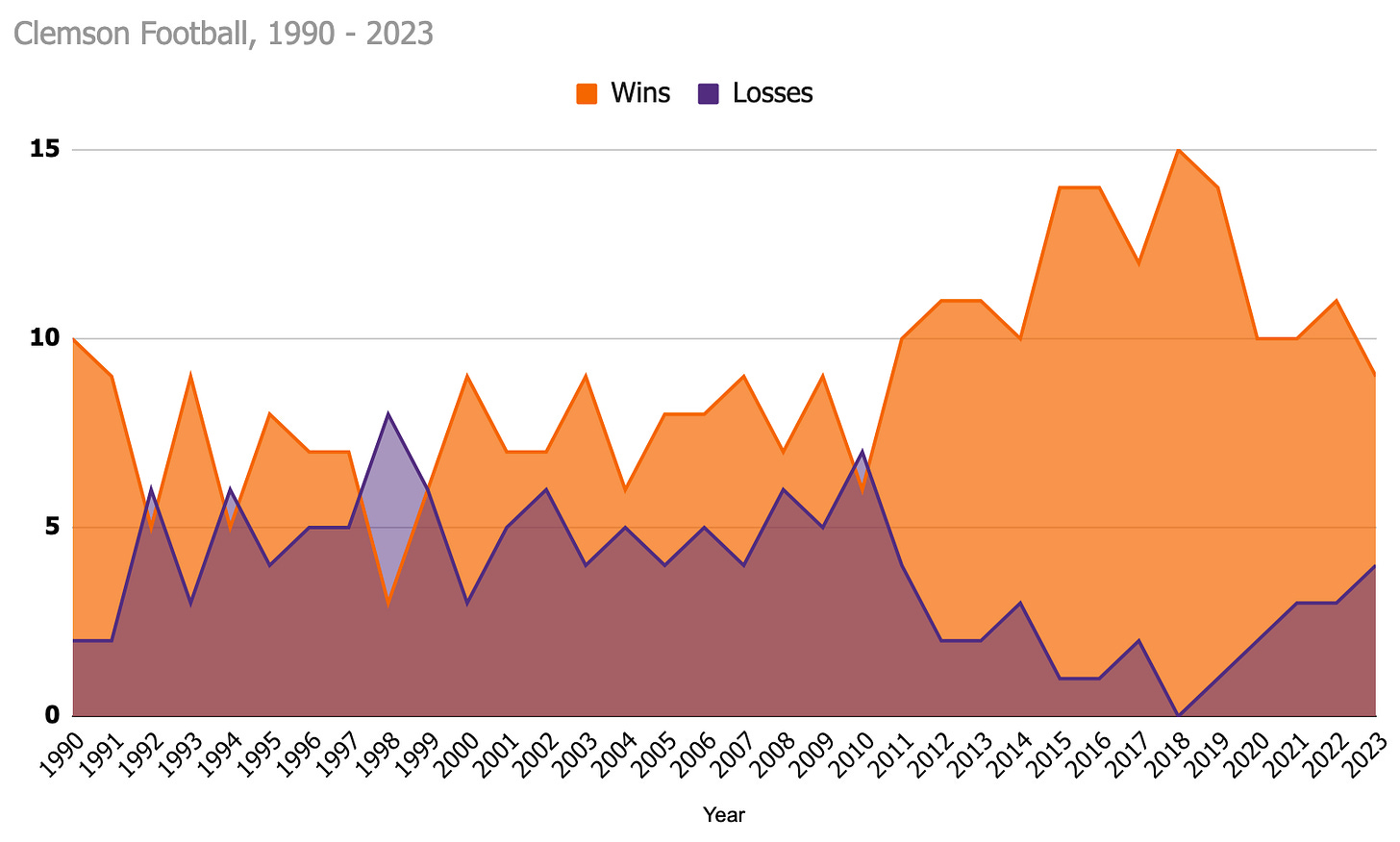

The football program at Clemson University provides a great example of an organization that demonstrated a profound pivot and is now facing some challenges to its own success. From 1990 to present day, Clemson has employed four head coaches: Ken Hatfield, Tommy West, Tommy Bowden, and widely-known Dabo Swinney. From 1990 - 1998, Hatfield and West predominantly deployed a heavy run-first, control the ball style of play calling. From 1999 to 2008, Bowden began experimenting with more spread, balanced offensive designs before transitioning to Swinney’s throw first designs. Over those periods, win rates moved from 60%, to 61%, to 80%, respectively. Moving from relative obscurity into regular contention for conference and national championships is a dramatic shift.

Yet, over the past few seasons, the on-field performance has struggled amidst a shift in conferences and competitors viewing the transfer portal and NIL funding as a recruiting opportunity. Swinney, like many well-tenured executives, views the changes with a bit of skepticism. That’s fair - because recent results point to above average performance. But, the landscape of many environments have drastically shifted in recent years. The competitive and structural questions facing college programs are not too dissimilar from those facing the rail industry. To win in a persistently competitive trucking environment, with shippers facing higher (and normalized) manufacturing expenses, and consumer expectations for usability increasing, the rail industry will have to truly get out of their own way to innovate.

Inertia is the enemy of innovation. We most often experience corporate inertia as meeting bloat, multi-week analyses, stakeholder discussions, and general organizational velocity slowing down. One of the very best examples of the inertia anti-hero is Nvidia. For most of Nvidia’s history, it has survived (not thrived) on the basis of adapting to market trends quickly. In the late 90s, it almost lost the video game industry to 3dfx. In the early 2000s, it lost out to ATI for developing components for the Xbox 360. The global financial crisis of 2008 threatened the growth of the laptop market. At every stage, Jensen Huang has demonstrated a hunger and focus on things that are really hard, and an ability to do them at a speed nobody else can match. To be clear, this is about true, enduring innovation: progress over press releases, habits instead of headlines, results before recognition.

For a very long time, Nokia was more well known than Nvidia but their paths diverged in the early 2000s when Nokia struggled to respond to the emerging market of smartphones. At one point, Nokia was estimated to have over 90% market share and began experimenting with touchscreens and embedded phones. It is easy to point to the 2007 release of the iPhone as the beginning of the end - but that minimizes the fact that Nokia was sitting on one of the largest cash positions in the largest growth market in the world. What happened? The company was blindsided by its inability to respond to changes in both the market and consumer preferences. Years later, interviews showed that it was internal challenges, not external competition, that resulted in Nokia’s fall. One executive, speaking confidentially:

We were too slow to act.

There is a lesson here for all of us: inertia kills innovation. Whether it is college football, corporations, or emerging markets, the real challenge isn't the pace of change, but an organization's unwillingness to adapt and adjust quickly enough that leads to difficulties. With college football ticket sales up 50% since 2023, maybe there is a lesson that as the seasons change, so should we.