Go see your people

Despite successfully unwinding the storied post-industrial revolution style of working in 2020, the perspectives on office, hybrid, and remote work continues to draw research interest, discussion, and clicks.

As a company that was starting up just as nearly the rest of the world was shutting down, remote work has been an integral part of Telegraph’s DNA from day one. However, there is an intrinsic value to the moments that individuals share in person. Proximity can often breed productivity. These are often the moments when serendipity strikes; a simple conversation starts the process which evolves into a groundbreaking solution.

We were fortunate to see this in action a few weeks ago during our annual company-wide hackathon in Chicago. One of the most impressive parts of bringing a talented and diverse team together is the sheer impact of co-location. In any environment, this can often be a force multiplier in that working together, in person, lowers the barriers to information. Context isn’t buried in pages of a product requirements document; clarity isn’t lingering between two functions in the code block. More often than not, relevant information is not distributed in a tightly controlled process, but in an informal conversation between teammates. This often reminds me of the dialogue between Larry Page and Jonathan Rosenberg (from How Google Works) discussing a planning cycle being drafted and driven purely by the product team.

“Have you ever seen a scheduled plan that the team beat?” [Page] asked. Um, no. “Have your teams ever delivered better products than what was in the plan?” No again. “Then what’s the point of the plan? It’s holding us back. There must be a better way. Just go talk to the engineers.”

Education as experience

Yet, the notion of simply exploring the possibilities with your teammates isn’t exclusively a concept at Google. Nor is it an organizational principle limited to technology companies. At any railroad today, the majority of the solutions to operating problems are known; you just simply need to go ask the engineer: about the switch move, about the brake shoes, or the ballast.

Management training programs are something of a corporate holdover from an earlier period when enigmatic organizations were brands that produced exceptional products and, often, exceptional leaders. General Electric is often lauded for its leadership development process, which offered technical education, field exposure, and true, in-the-moment experience. Railroads have continued a similar tradition of taking in new graduates, or experienced leaders from other fields, and molding these groups of talent into functional operators prepared for both the career and lifestyle of railroading. Aside from rotations to various departments, these programs also include a heavy and thorough portion of on-the-job training, where the most willing students find themselves calling signals in a locomotive, changing a coupler, or handling a spike maul. During these multi-week evolutions, the heartiest of leaders would often respond to inquiries with, “Figure it out. Go talk to the engineer.”

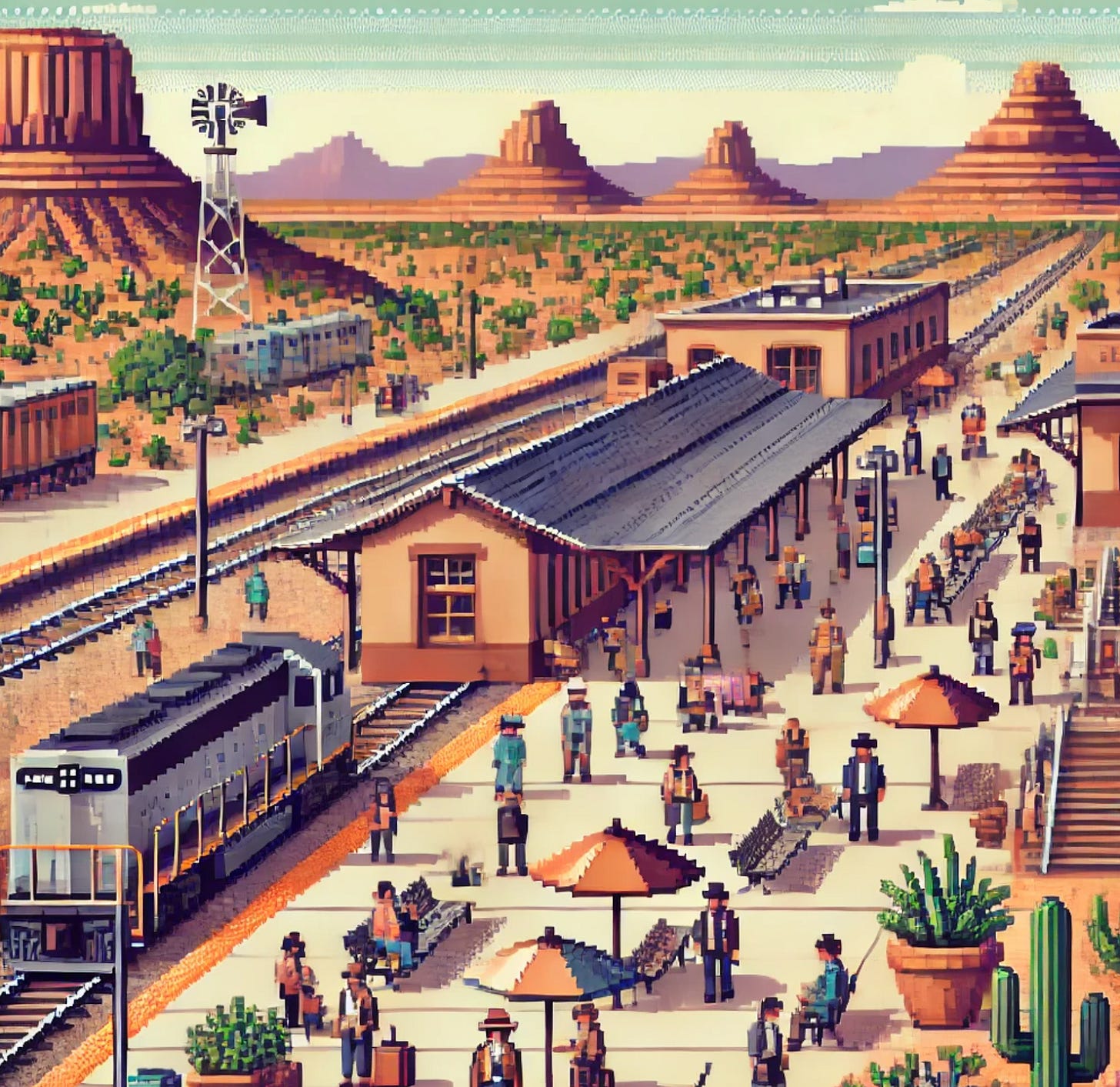

That was my experience during a hot summer spent in New Mexico. The expansion of Phoenix had begun in earnest, and a new intermodal service was required to combine traffic from Chicago and portions of Texas and the Southeast. At the time, the most respected and service-sensitive trains were given a designation of “Z9”, and the Clovis to Phoenix was one of the most prominent at the time. In order to meet the emerging demand in the perennial boomtown of the southwest, BNSF Railway would combine intermodal blocks from a variety of origin points in a remarkably quiet town just ten miles from the Texas border.

Culture cascades

Historically, railroads have leaned heavily on some of the most strategic tacticians in the space, known as Service Design teams, to garner the most productivity out of a precise and discrete physical network. Because of the natural design of how railroads were built and eventually bought and combined, a handful of natural processing points emerged, like Kansas City or Atlanta. Yet the desk jockeys at headquarters relied extensively on their relationships with individuals in the field who, simply put, made it happen.

BNSF Railway has perpetually maintained a strong “bias for growth”. The Clovis terminal superintendent at the time, Rick Smith, embodied that phrase entirely. In fact, he is one of the most hard charging and entrepreneurial railroaders I’ve ever met. A “bring it on” mindset defined his decisions and, if it could not be done elsewhere, he invited work from other parts of the network into Clovis. This swagger permeated the territory and terminal. When it was decided that the Phoenix traffic would be purified in Clovis, Rick took me out on the stoop and explained how he thought the switching moves would need to work. As was his style, he was often descriptive rather than prescriptive. When it became clear that I was more than confused, his advice was simple: “Go see the crews.”

With that, an education began, under the ever present sun of the Llano Estacado. What looked like a simple puzzle on paper evolved into an exposition of real world considerations: potential late arrivals, possible bad orders, and the fixed limits of the switching leads. With every solution, the crews would present another challenge: a signal failure, track out of service, or buried section of priority railcars. Eventually, the crew revealed a plan that would leverage two yard tracks and a switch known locally as the “5/10” or “the pocket” implying a sly usefulness. With some abruptly handwritten switch lists and some brusque language, the switch crew took me aboard and easily demonstrated the concept of block swapping without having to use either switching lead. A lengthy set of long, drawn out moves which would have taken an entire shift was reduced to a handful of hours. A bias for growth isn’t simply a phrase peddled in the media - it was an operating philosophy that created a desire for employees to earn the business of every single rail shipper in North America.

Yet the “pocket” switch wasn’t widely noted on every yard map. Like most solutions, the answers were not written down in a playbook, SOP, or inline comments within the codebase. The answers are with your people. And, in most cases, your best people are the ones closest to the challenge.

We’ve made it a habit of going to see our people at Telegraph. Naturally, the phrase represents our team members first. While logistically challenging and time-consuming, our leadership team makes an effort to visit every employee individually throughout the year. Time and progress have yielded growth and, at some point, this notion will not be reasonably feasible or prudent. Yet, we know and believe that our team today defines the future tomorrow. The phrase “your people” is not exclusive to your direct group of team members, it extends to the broader set of stakeholders. In fact, some weeks, the Telegraph team spends more time with each other while we are on-site with a customer than in our office. Many opportunities have been uncovered in the morning operations meeting, and equally, if not more importantly, many solutions have been devised over napkins and hand-gesturing in places that have become second homes to our team.

This notion readily applies to all stakeholders: investors, champions, and business partners. Thinking about capitalization? Sit in an investor's office. Want to understand how a vendor will handle your business? Spend the day with their team. We continue to do both, and are a better organization because we continue to invest time, effort, and energy into meeting people physically.

Many more articles, research papers, and opinions masquerading as “thought leadership” will be written about the benefits and drawbacks of remote versus in-person work. Many organizations will defer to hybrid as a natural reconciliation between the two, in an attempt to balance perceptions of comprehension and productivity. There is no ideal solution for every person or every company at every stage. The truth is: the work is the work. The antidote to miscommunication and misunderstanding is clarity. The most efficient path to clarity is proximity. The undeniable aspect of proximity is that it physically represents and reminds us that we are a team. None of us will accomplish as much individually as we can with our people.

Turn off the screen. Board the train or plane. Go see your people. You won’t regret it.

Thanks for reading Signal Indication! Subscribe for free to receive new posts.