Straight up

What a difference a decade makes. Nearly ten years ago, Canadian Pacific (with the backing of Pershing Square) made an offer to acquire Norfolk Southern for a 50/50 cash and stock transaction valued at roughly $28 billion at the time, less than half of the $71.5 billion Union Pacific is now prepared to pay for the same franchise. What ensued could have created an anthology of The Barbarians At The Gate. Letters, proposals, and an endless litany of presentations were met with the sound and reasonable responses from NS, which offered “grossly inadequate” as a succinct response. Aside from the limited interchange traffic, lack of Chicago bypass routing, and CP’s prior record with labor and shippers, it was hard for government agencies to support the review. The Surface Transportation Board received over 100 letters in opposition to the potential merger with prominent organizations like UPS, FedEx and other companies with a significant rail portfolio.

The final statement from the Department of Justice barely registered over the chatter in the halls and through statements on the calls: The strategy NS had to serve its shippers and return the value to shareholders was stronger than anything presented. While there was certainly a fiduciary duty to evaluate the opportunity, the company’s confident approach signaled clear independence.

This time, however, there was a notably muted response. Instead of a unifying message from the executive team, the merger rumors of the past few weeks were left to fester. Silence has a way of becoming its own statement. The news was cemented early on July 29th with the handover of Norfolk Southern’s earnings call to Union Pacific CEO, Jim Vena. The potential tie-up would yield a network covering nearly 50,000 miles of track, combining NS’s ~19,300 route miles with Union Pacific’s ~32,400 route miles into the first true coast-to-coast Class I system in U.S. history. Topics from the call included history, legacy, network reach, single-line service, cultural alignment, revenue multiples, and of course, service. The possibility of the combination is intriguing, but I certainly feel for the employees who have spent the past decade fighting through a litany of distractions in an effort to provide customers with a consistent product. But more than anyone, I feel for rail shippers: the ones paying the bills, who have been increasingly frustrated for many years. Ironically, of roughly 21,000 words spoken during the call, 'shipper' was mentioned only three times.

Bigger network, same problems?

For an industry where “growth” has embedded into the corporate vernacular more than any other phrase, this was an interesting belief that the path to an “up and to the right” future may not be from a compelling service product. Rather, it is consolidation. For shippers accustomed to waiting for improvement, the announcement probably rings like the chorus of Paula Abdul’s “Straight Up” asking for clarity, which may never come.

Dissatisfaction with rail service has, to an extent, become a meme unto itself. Yet, in the past year, shippers have started airing their concerns beyond industry committees and advocacy groups. Historically, seeing a shipper on stage at a rail industry conference was rare. Many avoided the spotlight, wary of being inundated by vendors and railroad representatives sustaining the insular conference circuit. However, that has shifted with one shipper recently remarking, publicly, “I can’t think of any other industry where it is so combative between customer and supplier” to a room full of head nods. The sobering reality that many rail customers have shared is their desire to leverage rail more is ironically being met with service reductions, increased accessorials, and unresponsive contacts.

Unfortunately, a transcontinental merger may not change that perception.

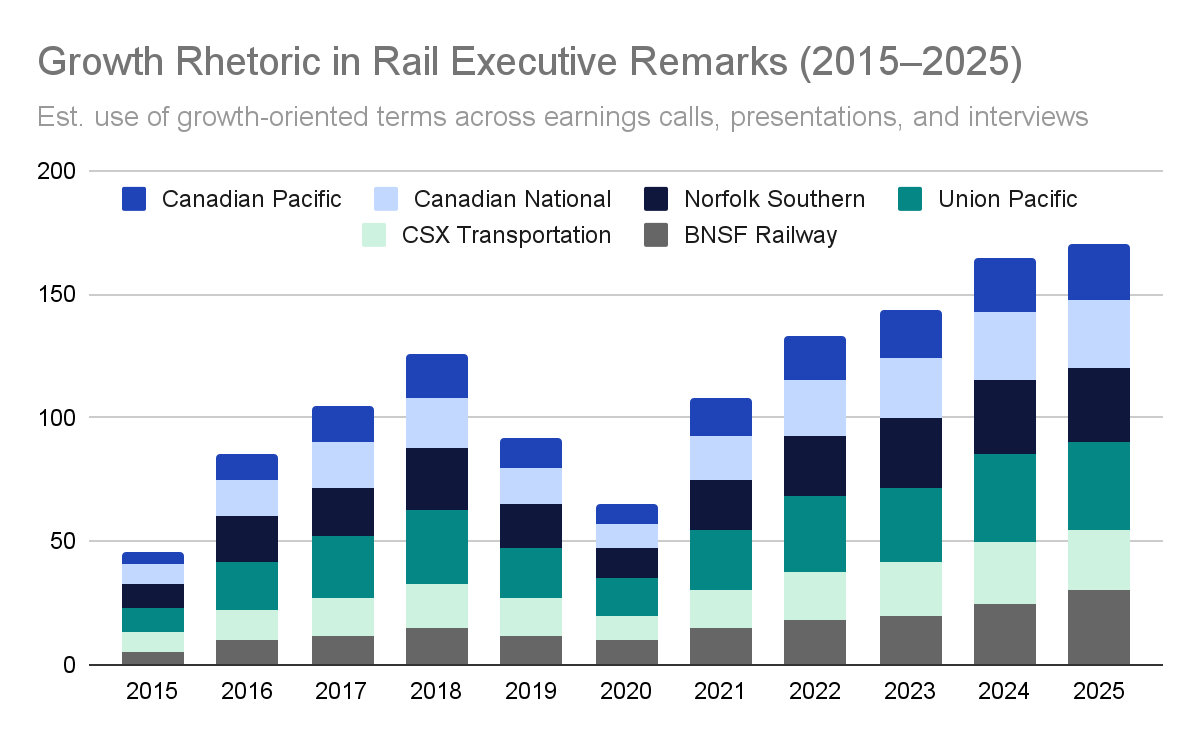

Over the past few years there has been something of an anecdotal relationship with an increase in railroads discussing their willingness to “partner” or that they were posturing as “open for business”. Yet, in that same time, the amount of shipper candor around the reliability and consistency of both carload and intermodal service has grown significantly.

As good as it gets

In fact, if you review the number of times executives used growth-oriented language in public forums (earnings calls, investor presentations, interviews) there is a staggering uptick, especially from 2022 onward. However, with the potential combination looming, the industry may be communicating something altogether different: this is, in many ways, as good as it gets.

For years, railroads have tried to balance constituencies with wildly different expectations, incentives, and time horizons. The operating ratio, a once-potent lever, has been pulled to exhaustion. You cannot cut your way to growth. This truth has become painfully clear as we enter the third year of a freight recession. Imports and domestic production continue in an uneven fashion (some projections call for another 14–16% YoY decline in the first half of 2026), an overhang that even a merged network will struggle to overcome without substantial share gains and truck-to-rail conversion.

Operational metrics like dwell and train speed may look solid, yet cycle times, carload service, and intermodal availability remain under pressure. For shippers, who plan networks over long-term horizons, rail’s value proposition rests on stable, affordable, and consistent service. This often conflicts with the 90-day performance demands of the investment community. After a decade of tension between these perspectives, the industry’s implicit conclusion appears to be that the cost of sustained, organic growth is too high. And so, we merge.

Relentless, with results

Putting aside all the scenario modeling flowing like quicksilver and “what about” prognostications from expanding the rail consulting class, the most admirable aspect of this entire ordeal? We finally got to see the speed at which railroads can truly enact change.

To their credit, Union Pacific has executed a relentless, full-court press. The strategy appears to be twofold:

As the first mover, UP sets the baseline valuation. If there is to be a wave of mergers, the first deal will be the cheapest.

If a bidding war pushes Norfolk Southern’s price too high, UP could pivot to CSX, arguably a franchise with equal or greater potential depending on the metric.

Debt capacity and credit ratings will be tested, but analysts suggest UP could secure the financing and weather a downgrade, betting on expanded reach and scale efficiencies. Some estimates indicate at least a 10-year discounted payback period. Kudos to the entire UP team for accelerating into an “all gas, no brakes” role, despite a lack of immediate financial certainty.

Considerations on competition

Over the next ~15 months of the formal review period, we will hear many interpretations or definitions of competition. When the STB weighs options we will hear various framings: “effective” or “intramodal” or “feasible alternatives” and potentially even “constraints” but ultimately the review will move past abstract, philosophical terms. Based on its own merger review rules, the STB defines the threshold as whether a transaction would “enhance competition” or, at a minimum, preserve competitive options for shippers and communities. This framing is likely to include preventing a loss of independent routing choices, ensuring service (and rates) remain commercially reasonable, while safeguarding against any single carrier gaining undue market power over captive shippers. This test is generally rooted in the public interest standard, which is a remarkably high burden to achieve.

By that measure, the proposal will likely be scrutinized through a few lenses:

Routing / Redundancy: Would the new, combined network offer viable competition on key corridors or regions, or would certain origins / destinations become de facto monopolies?

Market Power: Does the combination reduce the number of competitive options for specific commodity markets? Nearly half of the chemical industry is served by only one carrier; will this increase the proportion of captive shippers in other markets?

Service Quality: Will the combined entity have a credible and enforceable plan to maintain (or improve) service levels, and whether the plan can be reasonably measured or enforced on a long horizon?

Considerations on concessions

The other major rail carriers are unlikely to remain passive. One of UP’s strategic actions was to consistently press for a move from Berkshire / BNSF. Yet, even in a continued patient posture, BNSF could pursue alliances or a direct CSX bid. One of the benefits of Berkshire Hathaway’s cash reserves is the relatively unfettered access to capital relative to the undulating debt market. But, in this case especially, ease should not be confused with easy.

The Canadian operators (CN, CPKC) are the true wild cards. Considering some prior overtures between BNSF + CN, there could be an attempt to reinsert itself in a broader U.S. east-west market in the event of new interchange or trackage opportunity. In doing so, CN would likely provoke a move from CPKC, which despite its recent north-south expansion would seek gains as well.

Ultimately, if an approval is truly considered, the following are areas where conditions are likely to arise:

“Open” Gateways: In an effort to maintain shipper access to alternate carriers, certain interchange points may be forcibly required to have multiple interchange partners.

Trackage Rights: Potentially a broader overlay of where competing railroads will be provided an opportunity to offer service via a competitor's line. In theory, this could be a precursor for reciprocal switching, but is most likely to be broadened for full train service.

Commodity Protections: A limiting factor or upper threshold on price increases for specific sectors like chemicals, energy, and agriculture.

Short lines, long game

Of course, there is a unique opportunity for the regional and short line carriers. They may be the only group positioned to win no matter how the Class I chessboard is rearranged. If the proposal moves forward, open-gateway rules, reciprocal switching, and trackage rights could channel more volume to short lines.

The task will be scaling without losing the agility that makes shortlines valuable. That could mean upgrading track for heavier cars, adding new facilities, tightening links with ports and industrial parks, or offering some expanded switching services. In a market obsessed with “billy” dollar deals, the most dependable service might come from operators measured in carloads, not stock price.

Next stop?

The rail industry has always had a talent for promising transformation while delivering something far more incremental. This time, the stakes feel different. The current proposal (and its intentions) force the ecosystem to truly consider whether the future is built through the virtuous cycle of service <> growth, or simply stitched together by acquisition. For all the strategy decks, earnings calls, and breathless headlines, the test will be measured not in near-term shareholder returns but in whether shippers see tangible improvement in cost, consistency, and capacity.

Shippers have been asking: “Straight up, now tell me…” for years. The answer will depend ultimately on how the industry confronts the trade-offs between growth on paper and growth on the ground.